Early one morning in August 1535, a twenty-nine-year-old gentlewoman and her maid boarded a wherry and were rowed three miles along the River Thames to London Bridge. They paid the oarsmen and climbed the steps from the river, walking until they reached the north tower before the drawbridge. Looking up, they would have seen the dozen or more skulls on poles protruding from a ledge of the parapet, parboiled and coated with tar to prevent the circling, screaming gulls from scavenging them.

The bridge-master’s door opened to admit the women. After a brief conversation, the maid unclasped the purse and handed over some coins. In return she received a skull, which she gently wrapped in a linen cloth before putting it in the basket.

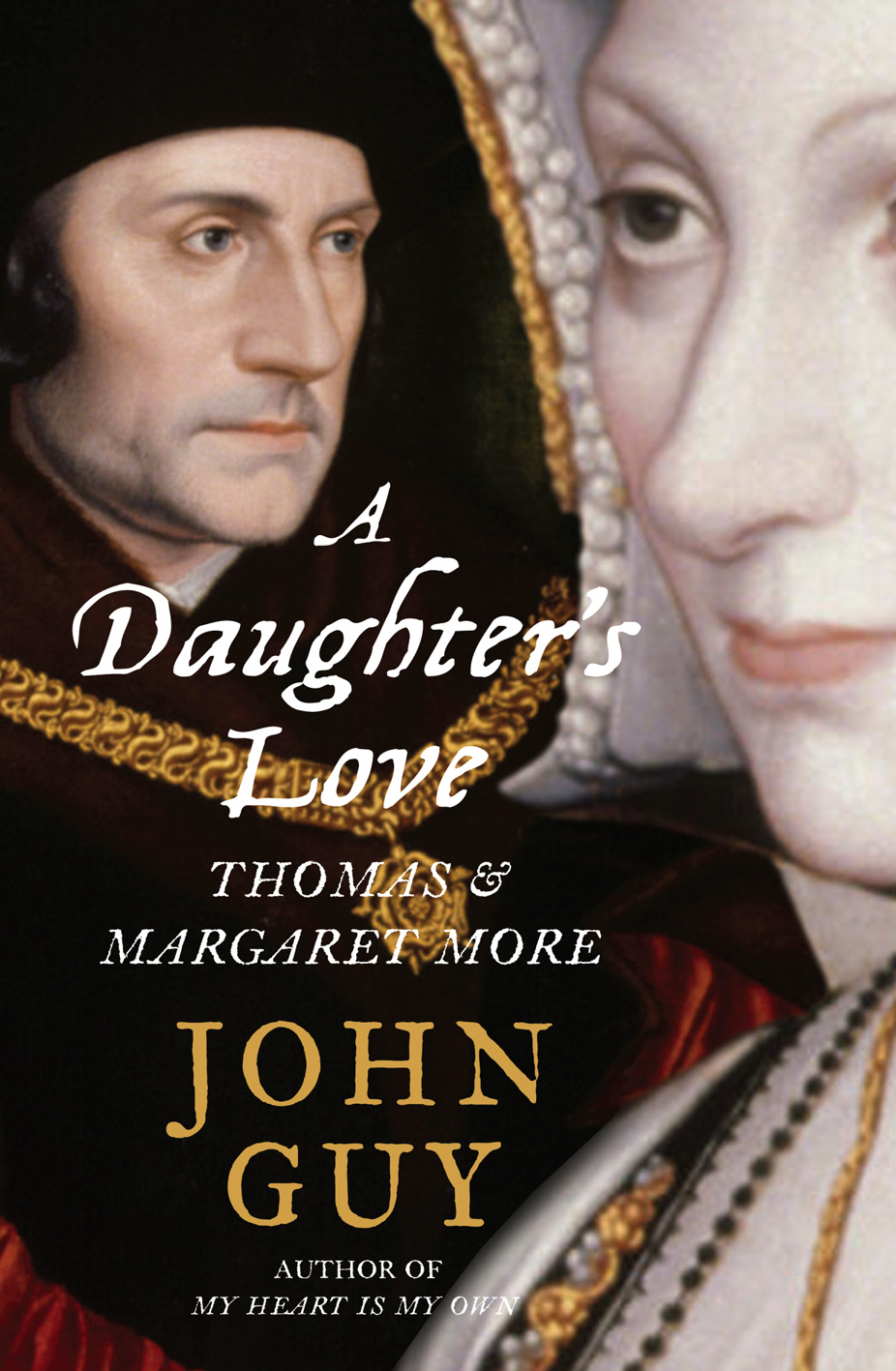

The gentlewoman was Margaret Roper, her maid was Dorothy Colley, and the head they had surreptitiously recovered that of Sir Thomas More, Margaret’s father, executed just over four weeks earlier.

The life of Sir Thomas More is familiar to many. His opposition to Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, his arrest for treason, his silence under interrogation and subsequent execution make up one of the most famous stories in British history. While More’s place in history is secure, Margaret, his daughter, has been almost forgotten. She was airbrushed out of the story, even though she played a leading role in this very public drama.

During More’s imprisonment in the Tower of London, Margaret became his sole intermediary with the outside world. She visited frequently, and the pair wrote long and loving letters to one another. Margaret also smuggled more inflammatory letters in and out of the Tower during these visits, and it is through such encounters that we see a dramatic new portrait of Sir Thomas More emerge.

Margaret lived in a patriarchal society, where gender stereotypes required women to be ‘chaste, silent and obedient’. Besides shockingly contravening that stereotype by writing and publishing a book, a step by itself as dramatic and inflammatory in its own day as anything said by her father in Utopia, her later interventions in her father’s cause were rightly seen as a threat by men like Thomas Cromwell, fully aware of the danger to Henry VIII if she were ever allowed to tell the whole truth. In spite of prudently dissembling, saying that she had hardly any of her father’s books and papers, her enduring achievement would be to make sure that these very same materials, and a great deal more, would one day be published, so that everyone could know the story of the man who’d kept silent. Published on 1 July 2008 by Fourth Estate (UK) and in 2009 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (USA).

An ebook of A Daughter’s Love will shortly be published in the UK by Penguin Books.

Reviews

- New York Times

- The Sunday Times

- The Independent

- The Sunday Telegraph

- The Independent on Sunday

- The Tablet

In his biography of Thomas and Margaret, John Guy brings Margaret conclusively out of the shadows … Guy’s convincing page-turner of a double life has restored my faith in biography as a genre. The fact is, if you are as capable a historian as Guy is, with as thorough a command of all the archival and printed materials associated with your subject and a scrupulous respect for the evidence, you can still produce a wonderfully fresh account of even such a well-known character as More.

Lisa Jardine, The Sunday Times

…absorbing and profoundly moving…

Helen Castor, The Sunday Telegraph

John Guy has written an admirable account… the result is a minor masterpiece.

Jonathan Sumption, The Spectator

…absorbing, thoroughly researched…

Claire Tomalin, New York Times